It’s not very often that I get the urge to write about a book on economics, but Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist is too interesting to miss out on. It’s a fascinating and thoroughly readable book by Kate Raworth which argues that modern economics is in trouble and in need of a serious rethink. In the wake of huge financial crises, widening inequality and an obsession with economic growth which is putting the natural environment under increasing pressure, Doughnut Economics asks ‘what might a more just and sustainable economic system look like’?

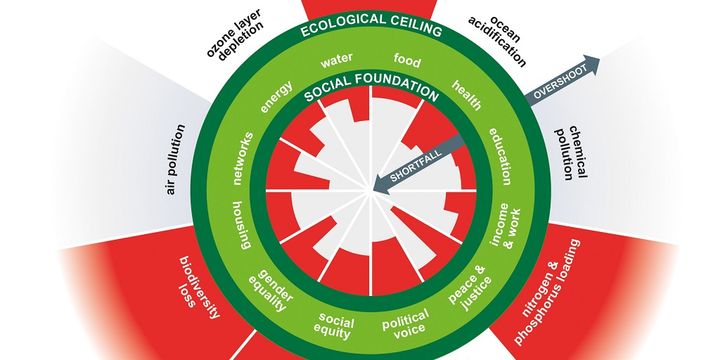

Kate doesn’t provide one all-encompassing answer to that question but instead explores a variety of possible solutions (and parts of solutions) that have great potential. And, perhaps more importantly, she provides the shape these different solutions should fit into, namely: the doughnut. That is, the "environmentally safe and socially just space in which humanity can thrive." The doughnut is a simple and bold reminder to reconsider what our economies are actually for: ensuring that everyone can meet their needs (food, housing, equality, etc.), without exceeding the means of the planet in the process.

The doughnut’s social foundations are derived from the United Nation’s 2015 Sustainable Development Goals while the planetary boundaries come from an international group of Earth-system scientists led by Johan Rockstrom and Will Steffen. If you click on or hover over any boundary or foundation on the diagram below you can see the data and metrics underlying each. Unfortunately, as you can see from just a glance, we’re already far outside the doughnut in almost every respect. But there is still hope!

So how do we get inside the doughnut?

The first step is to challenge the prevailing logic that the aim of any healthy economy should be never-ending economic growth as measured by increased GDP. Instead, Kate argues that the goal should be something more akin to "achieving human property in a flourishing web of life" which cannot be captured with a single, solitary metric like GDP. That’s not to say that GDP is irrelevant, but it is not the be all and end all; it paints an incomplete picture, and the success of our economy shouldn’t (and quite likely can’t) be tied to its perpetual growth.

Growth is, unsurprisingly, a recurring theme throughout the book and it is revisited in depth in the final chapter. The book’s conclusion is to be "agnostic" about growth by designing economies that can flourish "whether GDP is going up, down, or holding steady." That’s a significant change from what we see in most countries today, and it has some overlap with the degrowth movement. For poorer countries, increasing GDP might still be a crucial step in tackling poverty and meeting people’s needs, but for richer countries (like the UK) it may no longer be fit for purpose.

Many countries are attempting to decouple economic growth from environmental impacts via "green growth" (with some success) but we’re already so far outside safe planetary boundaries that it’s going to be very difficult, if not impossible, to shift rapidly enough to get us where we need to be and keep growing to boot. And while elements of green growth are important – particularly shifting energy infrastructure from fossil fuels to renewables – as growth rates in richer countries shrink, we may need to prepare for what Bank of England governor Mark Carney described in 2016 as "a low growth, low inflation, low interest rate equilibrium."

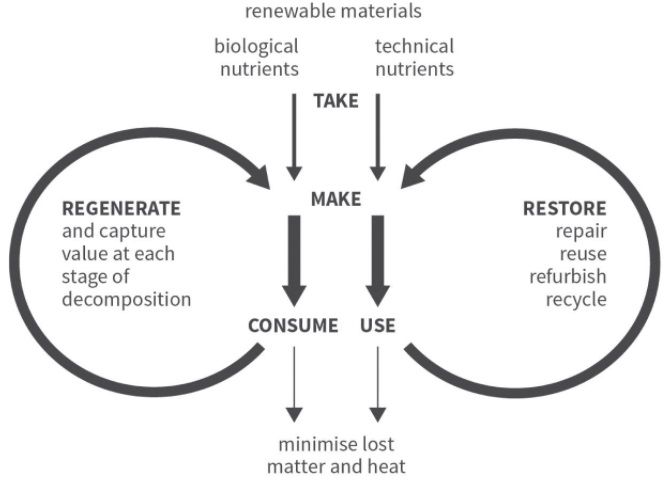

A crucial part of this puzzle is designing economies that are regenerative and distributive by design. For the latter, that means rejecting an exclusive focus on increasing GDP with the hope that wealth will "trickle down" from the few to the many, and embracing wealth that is distributed fairly from the offset. One way this could be improved is by diversifying the purpose and structure of businesses – away from the ubiquity of the external shareholder model (aimed solely at increasing value for shareholders) and towards more cooperatives, non-profits, community interested companies, and so on.

By embracing a unique "living purpose" (and even enshrining it in their articles of association) a company can make a firm commitment to pursuing more than just profit. Social justice and environmental sustainability should be key among these but for the latter, as Kate argues, what we really need is to go beyond a "do-no-harm" mindset and toward a regenerative one. With the world’s natural resources massively depleted already it’s not enough to stop making things worse, we also need to fix what has been broken, and set ourselves up for a sustainable future while we’re at it.

Here we can take inspiration from the likes of permaculture and Janine Benyus‘ ideas around "generous cities," both of which look to learn from nature and mimic patterns found in natural ecosystems. By doing so we can create self-sufficient systems that thrive on reuse and recycling (of materials, nutrients, energy, etc.) instead of ever-increasing inputs and waste outputs (industrial agriculture’s reliance on more and more fertilizer and herbicides, often to the detriment of the local environment, for example).

Rooftops that grow food, gather the sun’s energy, and welcome wildlife. Pavements that absorb storm water then slowly release it into aquifers. Buildings that sequester carbon dioxide, cleanse the air, treat their own waste water, and turn sewage back into rich soil nutrients. All connected in an infrastructural web that is woven through with wildlife corridors and urban agriculture.

There’s loads more packed into this book – including some economic history, thoughts on "the market" and its place in an embedded economy, the role of finance and the financial system, a replacement for the outdated concept of the "rational economic man," systems thinking and dynamic complexity, and more. Kate has some nifty animations on her website that give an overview of the book’s main concepts (I’ve embedded the first one below).

It may not seem terribly glamorous but, as Kate says, economics is "the mother tongue of public policy, the language of public life, and the mindset that shapes society." And improving our fluency might just help change the world.